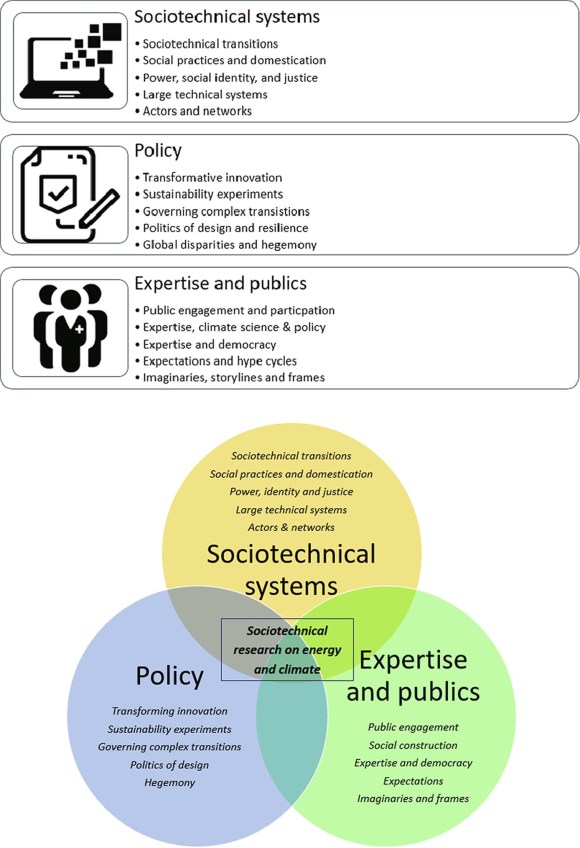

What will it take to address the crisis of self-governance of socio-technological systems at the heart of global unsustainability?

Clark A. Miller, “Sustainability, Democracy, and the Techno-Human Future,” in J. Hoff, Q. Gausset, and S. Lex, eds. The Role of Non-State Actors in the Green Transition: Building a Sustainable Future. London: Routledge. 2020.

What is sustainability? For many, it is the promise of bringing the human relationship with nature into balance. For me, this definition is wrongly directed. I find the human relationship with technology far more central to project of sustainability. Most of us regularly delude ourselves into thinking that we are just ordinary people: biological beings who go about our daily business of eating and drinking and reproducing; economic beings who work or buy or sell; political beings who vote. We are not. We have become techno-human. Like the borg queen, every decision and action that we take ripples outwards from us through rivulets of networked systems–part social, part technological–to create patterns of social and ecological footprints in the world. These systems evolve, grow, wither, and die bit-by-bit in response to the purchases that we make, the votes that we cast, the places we decide to go, and the paths that we choose to take to get there. It is these systems–systems that provide us with food, water, energy, stuff, shelter, news, data, mobility, and more–that are wholly out of balance. We choose not to see them as a part of ourselves (although we can sometimes measure their outputs, like the project to measure national inventories of emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere). We often choose not to see them at all. Our knowledge systems do not look for them, look away from them, in fact. We remain trapped in the imaginary of the human: we are individuals, we are populations, we are nations, we are markets, we are companies. No, we are borg. Until we wrap our heads around that fact, the project of sustainability is doomed.

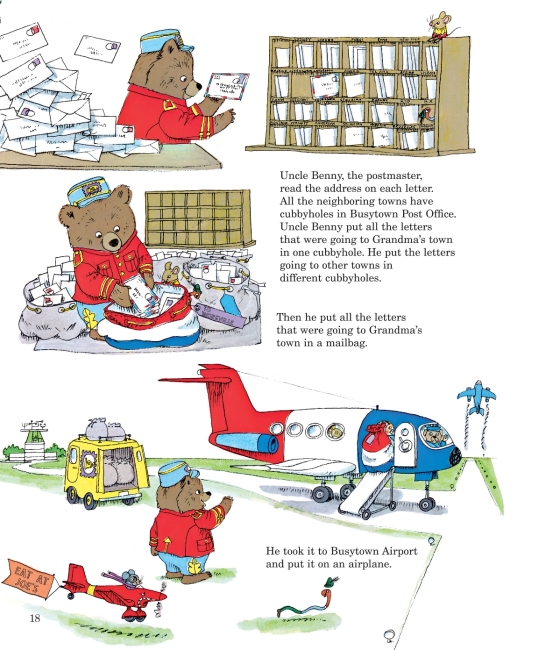

We have so badly misjudged COVID-19 because the scientific lenses through which we observe and attempt to make sense of reality actually impede our view of the world that the virus has infected. … the pathways carved by coronavirus have everything to do with how we have engineered the economies and societies of the twenty-first century.

Clark A. Miller, “A Plague Comes to Busytown,” Issues in Science and Technology. April 30, 2020.

Richard Scarry’s Busytown lies at the heart of the sustainability challenge. We lose sight of that fact at our peril.

Clark A. Miller, “What’s Up on Earth Day in Busytown?” Medium.

We have sculpted the technological highways and byways that have made it easier for the virus to reach some people and harder to reach others, that have made some people more vulnerable to its weapons while rendering critical protections to others.

Clark A. Miller, “Where’s Goldbug?” Issues in Science and Technology. April 30, 2020.

Can techno-humans govern the systems they have created for, and in which they have embedded, themselves?

Clark A. Miller, “Sustainability, Democracy, and the Techno-Human Future,” in J. Hoff, Q. Gausset, and S. Lex, eds. The Role of Non-State Actors in the Green Transition: Building a Sustainable Future. London: Routledge. 2020.

Busytown’s challenges are our own—its inequalities, instabilities, infections, and unsustainabilities—rooted in the design and organization of its webs of techno-human systems.

Clark A. Miller, “A World Made by Belief,” Issues in Science and Technology. April 30, 2020.